Towards a Theory of Power for Sustainability Science

The persistence of the climate crisis, ecological destruction, and grinding poverty in a time of unprecedented wealth share something in common: they are not primarily technical problems awaiting better solutions. They are problems of power.

The pursuit of sustainable development is, at its core, a massively redistributional agenda. It asks those who benefit from current arrangements to accept constraints on their behavior for the sake of others–including people in distant places and future generations who have no seat at the table. It should surprise no one that powerful actors resist such constraints. What should surprise us is how long sustainability science went without seriously examining the mechanisms of that resistance.

Power in Sustainability Science

Early sustainability science largely sidestepped questions of power. We developed sophisticated frameworks for understanding ecosystems, elegant models of resource dynamics, and increasingly nuanced theories of institutional design. We could explain how systems worked but struggled to explain why unsustainable patterns persisted despite widespread knowledge of their harms. When we encountered resistance to change, we fell back on vague gestures toward “political will” or “implementation challenges.”

More recent scholarship has begun to correct this. Researchers now increasingly recognize that maldistributions of power reinforce unsustainable development pathways, and a growing body of work grapples seriously with how power shapes sustainability outcomes. This is progress.

But here is the problem: this literature remains disjointed. It fails to build on itself or to converge around a common theoretical language. Different scholars use different frameworks, often drawn from different disciplines, making it difficult to accumulate knowledge or compare findings across cases. We lack a shared approach that would allow us to systematically analyze power dynamics across the diverse action situations that sustainability science addresses–from local fisheries to global climate negotiations, from urban planning to agricultural transitions.

I want to make an argument: we should adopt the three-dimensional framework of power, originally developed by Steven Lukes and empirically demonstrated by John Gaventa, as that common language. This is a bold claim, but I believe it is justified. The framework is theoretically rigorous, empirically grounded, and–crucially–it fits naturally within the broader conceptual architecture of sustainability science, connecting power to the actors, institutions, resources, and goals that already populate our frameworks.

Three Dimensions of Power

In my work with William Clark, we have argued that sustainability science would be well served by adopting a three-dimensional view of power, drawing on the foundational scholarship of Steven Lukes and John Gaventa. This framework reveals that power operates through distinct but interconnected mechanisms:

Compulsion is the most visible form of power–the ability to prevail in open conflicts. This dimension derives from ownership of or access to resources: land, capital, labor, technology, military might. When colonial governments extracted vast quantities of resources from their colonies, they did so on the back of superior military and economic power. When fossil fuel companies today fund political candidates who oppose climate action, they deploy accumulated wealth to compel political outcomes.

Exclusion operates more subtly, through the ability to shape institutional rules and norms–to determine what issues get on the agenda, who participates in decisions, and what outcomes are even considered possible. When industry interests limit the scope of environmental negotiations to exclude outcomes that would harm their bottom line, they exercise exclusionary power. The question is not just “who wins?” but “who decides what we’re fighting about?”

Influence is the most insidious dimension–the power to shape what others believe, want, and imagine as possible. When corporations fund disinformation campaigns that manufacture doubt about climate science, they exercise influence over public consciousness. When dominant narratives frame environmental protection as necessarily opposed to economic prosperity, they constrain what alternatives people can envision. The result is that many forms of unsustainability come to seem natural, inevitable, or beyond challenge.

Why the Dimensions Matter Together

The analytical power of this framework lies not in identifying three separate types of power, but in revealing how they reinforce one another to stabilize existing arrangements.

Consider the dynamics: An actor with compulsion power (control over resources) can use those resources to gain exclusion power (changing institutional rules to favor their interests). Exclusion power allows them to shape which issues are legitimate topics for discussion, reinforcing their influence over what others believe is possible. And influence power–by making current arrangements seem natural–reduces challenges to their control of resources, completing the cycle.

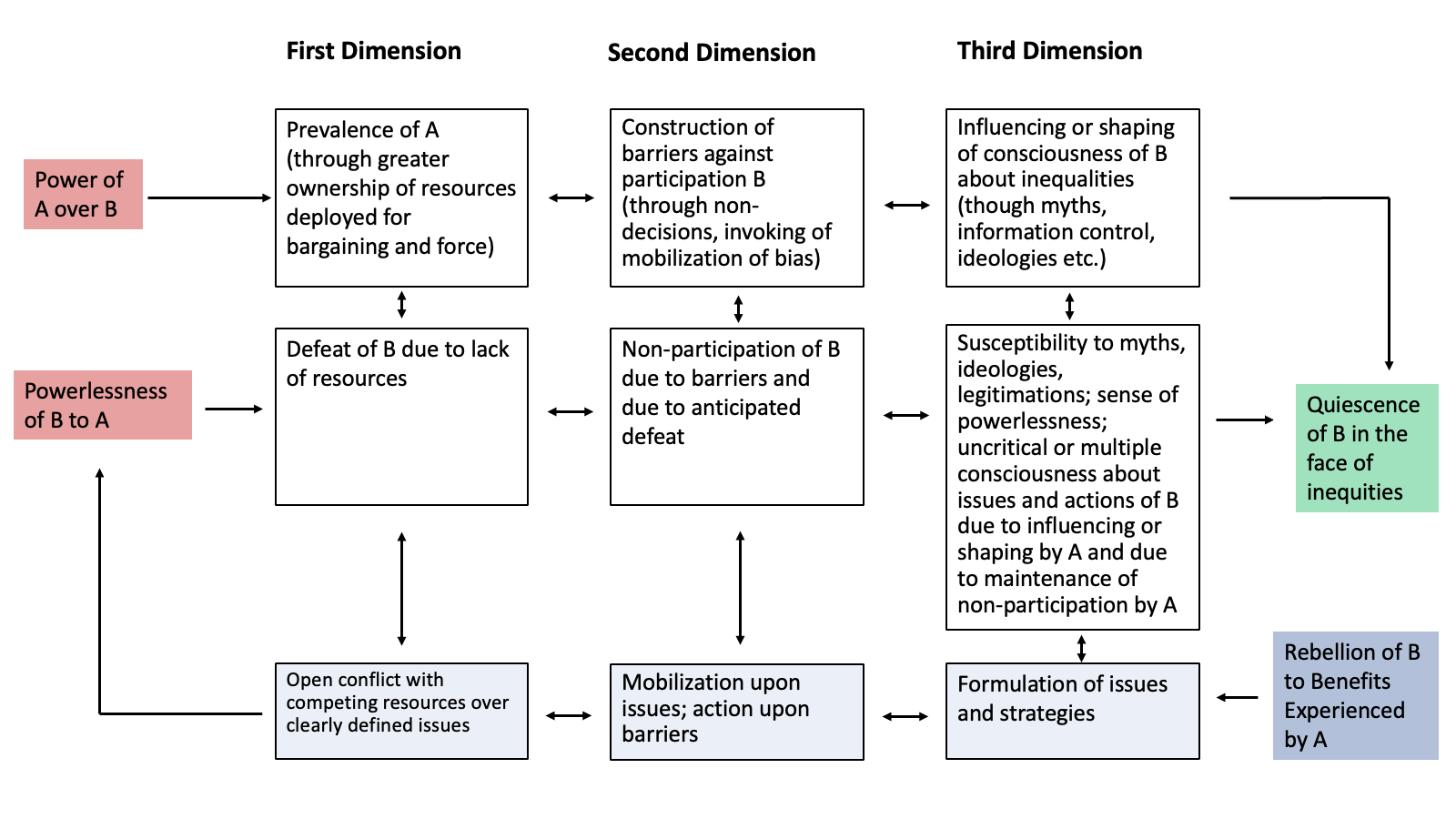

John Gaventa mapped these dynamics in his classic study of Appalachian coal country, showing how power and powerlessness reinforce each other across all three dimensions:

Figure: The three dimensions of power and their reinforcing dynamics. Adapted from Gaventa (1980).

The figure reveals something crucial: when powerful actors begin to lose their grip on one dimension of power, they mobilize their control over the other two to protect their interests until they can reestablish control. The arrows show how each dimension reinforces the others, creating a system that is dynamically stable–not static, but continuously reproducing itself.

This is what I mean by incumbency: the relationships among actors and institutions through which power differentials shape, stabilize, and reinforce existing regimes and their associated development pathways. Incumbency helps explain why so many sustainability problems appear “locked in”–not because better alternatives don’t exist, but because powerful actors work across all three dimensions to prevent those alternatives from gaining traction.

But the figure also shows the path to change. The bottom row reveals how each dimension can be contested: through open conflict over resources, through mobilization to change institutional barriers, and through the formulation of new issues and strategies that challenge dominant narratives. Successful transformation requires coordinated action across all three.

A Common Language for Sustainability Science

Taking power seriously has practical implications. It means that efforts to promote sustainable development cannot succeed through technical optimization alone. The most elegant policy designs will fail if they threaten powerful interests without strategies to overcome resistance across all three dimensions.

But my argument here is not just that power matters–most sustainability scientists would now agree with that. My argument is that we need a shared theoretical framework for analyzing power if we are to build cumulative knowledge. The three-dimensional framework offers exactly this.

I want to be honest about a limitation. Scholars working in the Foucauldian tradition would rightly point out that this framework still treats power as something that actors possess and deploy–something held by identifiable agents who use it to achieve their interests. Foucault’s insight was that power also operates diffusely, through discourse and knowledge systems, shaping what counts as truth and who counts as an expert in ways that cannot be traced back to any single actor’s intentions. The panopticon is not controlled by anyone in particular; it disciplines through the very structure of visibility itself.

This is a real limitation. The three-dimensional framework is better at analyzing power wielded by identifiable actors in specific action situations than at capturing the diffuse operation of power through discourse and knowledge regimes. For some questions in sustainability science–particularly those concerning how certain ways of knowing nature become dominant–Foucauldian approaches may offer more purchase.

But here is why I still advocate for this framework as our common language: sustainability science is, at its core, a practical endeavor. We study specific places and problems. We want to know why a particular fishery collapsed, why a particular climate policy failed, why a particular community was excluded from decisions about their land. For this kind of work–mapping who has power over whom, identifying whose interests are served by current arrangements, finding leverage points for change–the three-dimensional framework offers analytical traction that more diffuse conceptions of power do not.

Three features make it particularly suited to our purposes:

First, it is comprehensive. By distinguishing compulsion, exclusion, and influence, it captures forms of power that narrower approaches miss. Frameworks focused only on observable conflict (first dimension) systematically undercount power by ignoring how the powerful keep issues off the agenda or shape what others believe is possible.

Second, it is integrative. The framework connects naturally to the core concepts of sustainability science–actors, institutions, resources, and goals. Power mediates the relationships among all of these. Compulsion relates to resources; exclusion relates to institutions; influence relates to goals and narratives. This is not a framework imported awkwardly from another field but one that fits the theoretical architecture we already use.

Third, it is actionable. The framework does not just describe power; it reveals leverage points for change. Understanding that the dimensions reinforce each other also reveals that they can be contested across multiple fronts simultaneously–which is precisely what successful social movements have done throughout history.

No framework captures everything. But if we are serious about building cumulative knowledge on how power shapes sustainability outcomes–and how it might be redirected–we need a shared language. The three-dimensional framework is my candidate. I offer it not as the final word but as a starting point for the conversation our field needs to have.

This post draws on work with William C. Clark, especially our 2020 synthesis in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources. For the original formulation of the three-dimensional framework, see Steven Lukes’ Power: A Radical View (1974) and John Gaventa’s Power and Powerlessness (1980).

Further Reading: Applying the Framework in Sustainability Research

A growing body of scholarship applies three-dimensional power analysis to sustainability and environmental governance. Here are some starting points:

Kashwan, P., MacLean, L.M., and Garcia-Lopez, G.A. (2019). Rethinking power and institutions in the shadows of neoliberalism. World Development 120: 133-146.

This introduction to a special issue develops a “power in institutions matrix” that synthesizes multiple dimensions of power for analyzing institutional change. The authors explicitly build on Lukes to show how actors negotiate reforms through overt rule-making, agenda control, and discourse. The accompanying articles apply this framework across diverse sectors in Africa, Asia, and Latin America–offering concrete examples of three-dimensional analysis in development contexts.

Brisbois, M.C., Morris, M., and de Loe, R. (2019). Augmenting the IAD framework to reveal power in collaborative governance. World Development 120: 159-168.

A methodological contribution showing how to integrate Lukes’ framework with Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Design (IAD) framework. Applied to water governance in Canada’s oil sands and petrochemical regions, the paper demonstrates how powerful industry actors prevailed not only in direct conflicts but through agenda-setting and by reinforcing narratives that economic growth universally benefits communities. A useful model for revealing hidden power dynamics in collaborative resource management.

Clement, F. (2010). Analysing decentralised natural resource governance: Proposition for a “politicised” institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Sciences 43: 129-156.

An early and influential effort to bridge institutional analysis with power-centered approaches. Applied to forest policy in Vietnam, Clement shows how the third dimension of power–the shaping of values and beliefs–operates through daily enforcement of social practices. The “politicised IAD” framework she proposes has been widely adopted in subsequent natural resource governance research.

Gaventa, J. (2006). Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin 37: 23-33.

Gaventa extends his earlier empirical work into the “Power Cube”–a practical tool for analyzing how power operates across different spaces (closed, invited, claimed), levels (local to global), and forms (visible, hidden, invisible). While developed primarily for development practitioners, the framework offers sustainability researchers a way to systematically map power relations in multi-level governance contexts.