(In)equality ≠ (In)equity: Why the Distinction Matters for Sustainability

Strengthening the ability of sustainability science to grapple with issues of (in)equality and (in)equity requires working across deep differences in how people think about justice and fairness. Different philosophical traditions (e.g., libertarian, egalitarian, capabilities-based) come down differently on these questions. As do different religious and moral traditions. From the perspective of sustainability science, we are not here necessarily to adjudicate the ‘right’ answer to the question of what a fair or just distribution looks like, but as a field practically engaged with both intra- and inter-generational justice, we must find a way to talk about these concepts with as much clarity as possible.

This work gets harder when we fail to use consistent terminology and even worse when our terminology by virtue of the interdisciplinary nature of our field has been tangled that we often do not know how others understand the terms we are using for (in)equality and (in)equity. Untangling the meanings of these two terms and thinking through a pathway to using them consistently in our scholarship is well worth a try. Here is my own stab at figuring this out.

In both the scholarship sustainability science draws on, as well as in formal writing on sustainable development from sources as varied as the UN system, international NGOs and corporate sustainability programs, the terms in(equality) and (in)equity are often used interchangeably, or linked causally, or treated as if one is a subset of the other. Some of this confusion traces to scholarly traditions asking different questions and some emerges from how the terms get used in practice.

This post traces where that confusion comes from and argues for a cleaner framework for their use in sustainability science: First describe the distribution (equality or inequality), then evaluate whether it’s fair (equity or inequity). This framing is neither unique nor rocket science, but it’s surprising how often it does not seem to be used in either sustainability scholarship or practical efforts to foster sustainable development. The advantage of this approach, which I call the two-step, is that it creates space for people holding different theories of justice or stemming from different religious, moral and philosophical traditions to share empirical ground while preserving space for deliberation about what fairness requires.

The Two-Step Framework

My proposal which as I said before is neither entirely original nor rocket science, is a way to clearly distinguish important work that is descriptive of the world as it is, for the normative work of deliberating on the world as it should be.

(In)equality is a descriptive concept. It refers to measured distributions—of income, resources, health outcomes, environmental burdens, capabilities. Inequalities can be observed, quantified, and compared without yet making any judgment about their fairness.

(In)equity is a normative concept. It involves a judgment that some distribution is unfair or unjust—and making that judgment requires bringing a theory of justice to bear on the empirical facts. Crucially, people hold different and sometimes incompatible theories: what counts as unfair depends on whether you emphasize equal outcomes, equal opportunity, procedural fairness, sufficiency, or relational equality.

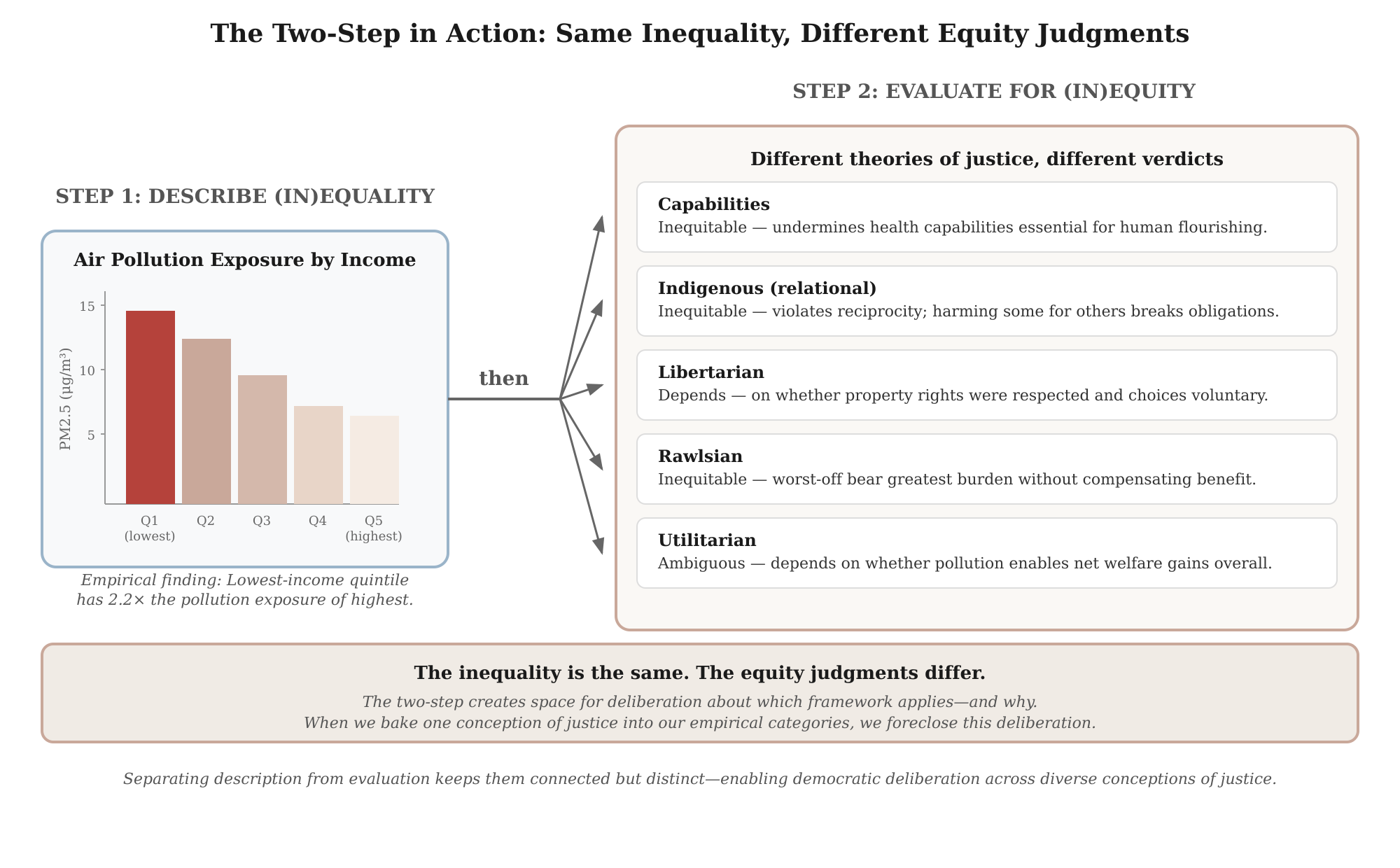

The same empirical inequality might be judged equitable or inequitable depending on the normative framework applied. A society with significant income inequality might be judged fair by a libertarian who emphasizes procedural justice and unfair by an egalitarian who emphasizes outcomes. The inequality is the same; the equity judgments differ.

The two-step locates normative disagreement where it belongs—in the open, as a site of deliberation—rather than hiding it inside measurement categories. This matters for sustainability science because we work across contexts where theories of justice genuinely diverge.

Why the Confusion Exists

A Starting Point: Two Pairs of Concepts

Before examining these sources of confusion, it helps to establish what we are working with. We are dealing with two pairs of terms appear to be grammatical opposites:

- Equality ↔ Inequality: sameness versus difference

- Equity ↔ Inequity: fairness versus unfairness

But this apparent grammatical simplicity hides a mountain of disagreement. As we will see, philosophers have long used “equality” to debate normative questions about fairness, not just to describe sameness. So while things may at first pass seem linguistically intuitive, the historical use of these terms even in careful scholarship is anything but.

What does seem clear (I think) is that the pairs can come apart. A distribution might be equal but inequitable (everyone gets the same despite different needs). Or unequal but equitable (people get different amounts for good reason). Equal does not mean equitable. Unequal does not mean inequitable. But even this argument is sometimes muddled in practice especially when the words are treated interchangeably.

The Baseball Fence and the Philosophy Behind It

One important source of the current muddle that I run into a lot is a viral image. In 2012, Craig Froehle created a simple illustration showing three people of different heights trying to watch a baseball game over a fence (Froehle, 2016). In the “equality” panel, each stands on an identical box; the shortest still cannot see. In the “equity” panel, boxes are redistributed according to need; everyone watches the game.

Figure 1: “Equality vs. Equity” illustration, adapted from Froehle (2016). See Note 1 for the image’s evolution.

The virality of this image taught a generation to distinguish equality as identical treatment from equity as differentiated treatment aimed at equivalent outcomes. The image does capture something real: an important philosophical debate about what fairness requires. But it does not capture a relationship between equality and equity as concepts. Understanding both what the image gets right and where it misleads requires tracing a longer philosophical lineage.

A long debate about fairness

Identical treatment doesn’t work as a standard of justice when people face different circumstances. Tracing this argument from Aristotle through Marx, Rawls, and Sen shows its philosophical evolution. (This philosophical debate has tended to use ‘equality’ language—formal versus substantive equality, equality of what?—but it’s fundamentally about fairness: what does justice require?)

In the Nicomachean Ethics (Book V), Aristotle distinguishes numerical equality—everyone receives the same amount—from proportional equality—distribution according to some relevant criterion such as merit or need. The insight is that “treating people equally” is ambiguous as a standard of justice. If people differ in relevant ways, giving everyone identical shares may itself be unfair. Justice might instead require proportionality: giving people what they are due based on the situation.

Centuries later, Marx sharpened Aristotle’s insight into a political critique. He argued that formal equality under the law actually perpetuates injustice. When the law treats the worker and the factory owner as formally equal parties to a contract, it ignores the vastly unequal circumstances that shape their bargaining positions. Marx’s alternative—”from each according to ability, to each according to need”—pushes towards a more egalitarian approach to the question of what fairness requires.

Rawls, in A Theory of Justice (1971), further developed the liberal egalitarian version. He distinguished formal equality of opportunity—careers open to talents, no legal barriers—from fair equality of opportunity, which requires that people with similar talents and willingness to use them have similar life prospects regardless of their social origins.

The economist and philosopher of development, Amartya Sen, addressed this debate by asking what exactly should we be trying to equalize? His 1979 Tanner Lecture “Equality of What?” and later Inequality Reexamined (1992) argued that focusing on income, welfare, or primary goods misses the point. Its not that these things don’t matter on some level, but to achieve true fairness Sen argues that we should instead focus on people’s capabilities—their real freedom to achieve functionings they have reason to value. A person with a disability may need more resources than others to achieve the same capability for mobility. This is the philosophical foundation for what Froehle’s second panel communicates visually: fairness means attending to what people can actually do and be, not just what they formally receive.

What the image captures—and what it distorts

The baseball fence illustration is effective because it makes this long debate intuitive. The first panel shows one theory of fairness: treating people fairly means giving everyone the same thing. The second panel shows another: treating people fairly means giving people what they need to achieve equivalent outcomes. Both are normative positions—both are answers to the question “what does justice require?”

In other words, both panels are about equity in the sense this post uses the term: normative judgments about fairness. The image does not contrast a descriptive concept with a normative concept. It contrasts two conceptions of what fair treatment requires when people are differently situated.

Notably, Froehle’s original image did not use “equity” at all. It contrasted “equality to a conservative” (same treatment) with “equality to a liberal” (differentiated treatment). His point was that equality itself is contested—people with different political orientations reach different judgments about what equal treatment requires. Later versions, not created by Froehle, relabeled the panels as “Equality” and “Equity,” stripping the political framing entirely and imposing a conceptual distinction Froehle never intended (Froehle, 2016). The viral mislabeling turned an argument about contested conceptions of fairness into an apparent contrast between two different kinds of concepts.

Froehle captured a real debate about fairness; the later re-labeling implied a conceptual distinction between equality and equity that does not map onto the philosophical tradition the image draws from.

The Public Health Tradition: Whitehead and the WHO

A second source of confusion comes from public health. In 1992, Margaret Whitehead published an influential paper, originally a background document for the World Health Organization, that defined health inequities as health inequalities that are “avoidable, unnecessary, and unfair” (Whitehead, 1992). This definition became canonical—cited over five thousand times and still the default starting point for health equity scholarship.

The Whitehead framing treats inequity as a subset of inequality: all health inequities are health inequalities, but only those that meet certain criteria—avoidable, unnecessary, unfair—count as inequities. The question becomes which inequalities belong in this subset.

This approach builds moral urgency into the category of inequity itself. To call a health difference an inequity, on Whitehead’s account, is already to have judged it unjust and actionable.

But the approach also embeds normative judgment into the term equity/inequity while leaving narrowing the space somewhat to deliberate on what justice looks like for different groups. What counts as “avoidable”—and who bears responsibility—depends on contested assumptions the definition leaves unresolved. The same is true of “unfair”: the definition does not specify which theory of justice underwrites its criteria (Norheim & Asada, 2009; Vallgarda, 2006). Later refinements, such as Braveman and Gruskin’s proposal to define inequity in terms of systematic disadvantage by social position (Braveman & Gruskin, 2003), resolve some ambiguities but build different normative commitments into the category.

This tradition is closer to the two-step proposed here than it might first appear—it is trying to be explicit about criteria for normative judgment. The difference is that the two-step keeps description and evaluation as separate steps, while the Whitehead tradition embeds evaluation into the category definition of (in)equity. For health policy within a single national context, the embedded approach may work well. Practitioners operating within the same political and legal system may share enough normative common ground that embedding judgments into definitions doesn’t foreclose important debates—the debates have in some sense already been settled for that context. But sustainability science works across cultural contexts and therefore requires collaboration among people holding genuinely different theories of justice. The field also engages intergenerational questions where we have limited agreed upon norms for what qualifies as intergenerational justice, and [add non-human point here too]. The two-step preserves space for deliberation; a definitionally resolved approach does not.

Causal Conflation

A third source of confusion emerges not from any scholarly tradition but from how these terms get used in practice. In corporate diversity programs, government equity frameworks, foundation strategy documents etc, people often assume a fixed causal relationship between inequality and inequity. Sometimes the assumption runs one direction: systemic unfairness produces unequal outcomes, so inequity causes inequality. Sometimes it runs the other: material deprivation leads to unjust treatment, so inequality causes inequity. Both causal stories can be true in particular cases. The problem arises when either gets generalized into a stable relationship.

Neither direction generalizes. The relationship is historically and contextually contingent (Hamann et al., 2018). Sometimes inequity causes inequality — discrimination produces unequal outcomes. Sometimes inequality causes inequity — material deprivation leads to unfair treatment. Sometimes they co-evolve, each reinforcing the other. And sometimes inequality emerges with no inequity involved at all — through luck, emergent dynamics, or the heterogeneous distribution of resources in complex systems.

The two-step sidesteps this tangle. Describe the distribution; evaluate its fairness. The causal story — however layered — is a separate question.

Three Framings, Three Different Questions

Tracing these threads it’s clear that these different framings are actually asking fundamentally different questions.

The Froehle/philosophy tradition asks: What are different conceptions of fairness? The contrast is between formal and substantive approaches to justice—same treatment versus differentiated treatment aimed at equivalent outcomes.

The Whitehead/public health tradition asks: Which inequalities demand action? The answer is those that are avoidable, unnecessary, and unfair. Inequity becomes a category within inequality, marked by meeting certain criteria.

Causal conflation asks: What causes what? The answer assumes a fixed relationship—either inequity causes inequality or vice versa—but no one seems sure which.

Figure 2: Three Framings, Three Different Questions

These framings are all in circulation leaving a tangled muddle of confusion for anyone trying to quickly write a report or develop a research project that engages issues of distribution, justice and fairness. The result is often conceptual muddle. Ive been googling the relationship between inequality and inequity now for several weeks and Google’s AI overview is constantly shifting slightly. One day the AI overview might assert that inequity causes inequality and another day that inequities are a subset of inequalities. Froehle’s image gets paired with causal claims it never made. Even legal scholars have noted the terminological instability; Martha Minow’s survey of the equality/equity debate in law and policy finds definitions shifting across contexts without clear resolution (Minow, 2021).

The two-step approach I’m advocating here keeps the empirical and the normative connected but distinct, and it keeps normative disagreement visible rather than resolving it definitionally. This approach uses the terms differently than many philosophers do—philosophers have long framed normative debates about justice using “equality” language. But for applied work, the two-step aligns with a distinction already implicit in how many researchers and some major institutions actually proceed. Making this convention explicit helps sustainability science. It preserves shared empirical ground for people who hold different theories of justice, while keeping normative deliberation visible and open. It’s a proposal about how we might use these terms more clearly, not a claim about how philosophers have always used them.”

The Limits of the Distinction

The two-step framework has limits. For many distributions—income, emissions, exposure to environmental hazard—reasonably neutral description remains tractable. But for some domains, the descriptive and evaluative are more thoroughly intertwined.

Michèle Lamont has argued influentially that inequality scholarship has focused too narrowly on material distributions while neglecting what she calls “recognition gaps”—disparities in dignity, worth, and cultural membership between groups (Lamont, 2018; Pierson & Lamont, 2019). This is an important corrective. But when Lamont identifies a “recognition gap” or describes how groups experience “stigma,” she is not making a purely descriptive claim the way Piketty does when he reports income shares. “Stigma” is not a neutral term. We use it because we already take concept to be unjust. In other words the very thing we are measuring already carries its normative freight built in.

Similarly, Hilary Putnam argued that the fact-value distinction, however useful, is not metaphysically clean—our choices about what to measure and how to categorize reflect normative commitments (Putnam, 2002). Science and technology studies has reached similar conclusions empirically: measurement categories and social order are co-produced, each shaping the other (Jasanoff, 2004).

The two-step framework does not rest on denying this entanglement. It claims that for many of the distributions central to sustainability science—who has access to clean water, how climate risks fall across populations, where environmental burdens concentrate—reasonably neutral description remains possible and valuable. For other domains—recognition, dignity, belonging—the framework helps us see that the descriptive and evaluative are more thoroughly intertwined, and marks those as requiring more explicit attention to the values our categories carry. In practice, this means that when working with recognition concepts, the two-step functions less as a method for separating description from evaluation and more as a reminder to be transparent that one’s “description” already carries normative weight.

How Careful Practitioners Already Work

The two-step is not a new invention. It appears most clearly in work on material distributions, where the descriptive task is tractable in ways it may not be for debates about justice itself.

Inequality economists

Thomas Piketty’s influential work on capital and inequality (Piketty, 2014, 2020) and the ongoing research of the World Inequality Lab use “inequality” consistently as an empirical, descriptive category. They measure income shares, wealth distributions, and carbon emissions by decile. When they move to normative territory—arguing for progressive taxation, wealth redistribution, or climate equity—they make those arguments explicitly rather than building them into their measurement categories. The term “inequity” rarely appears; the work proceeds by describing distributions and then making arguments about what justice requires.

Branko Milanovic’s work on global inequality (Milanovic, 2016, 2023) follows the same pattern: meticulous empirical measurement of distributions across and within countries, with analysis of mechanisms like the ‘citizenship premium’ and migration that shape these patterns. Like his peers, Milanovic explicitly avoids normative arguments about what justice demands, stating that his work is ‘indifferent to normative views regarding inequality’ (2023).

Major organizations

The World Bank is careful in its use of these terms. Its Poverty and Inequality Platform tracks distributions using the Gini index and other measures—empirical, descriptive work. When the Bank discusses fairness goals, it tends to use “equity” (as in “equity and inclusion”) or talks about “shared prosperity”. The term “inequity” appears sparingly.

Unfortunately, the UN has not achieved similar clarity. While SDG 10 is titled “Reduced Inequalities” and uses measurable indicators, the UN has not worked out the relationship between inequality, equality, and equity. A 2017 UN System framework document illustrates the confusion:

“This publication sets out a conceptual framework that includes equality (the imperative of moving towards substantive equality of opportunity and outcomes for all groups), non-discrimination (the prohibition of discrimination against individuals and groups on the grounds identified in international human rights treaties) and the broader concept of equity (understood as fairness in the distribution of costs, benefits and opportunities). It addresses both horizontal inequalities (between social groups) and vertical inequalities (e.g. income)… Intergenerational equity is also addressed, as are inequalities among countries.” (UN System Chief Executives Board, 2017)

Equality, equity, and non-discrimination appear as three parallel normative frameworks with near-circular definitions. “Inequalities” are things these frameworks “address,” but there is no separation between empirical description and normative evaluation.

Explicit theorization

Some scholars have already proposed this two-step process. In the health literature, Kawachi and colleagues (2002) articulate it directly: inequality refers to measurable differences in health outcomes, while equity involves normative judgments about fairness. In sustainability science, William Clark and I (Clark & Harley, 2020) also argued for this conceptual distinction: (in)equality as “a positive or descriptive concept referring to the distribution of assets or freedoms among actors,” and (in)equity as “a normative concept referring to the qualities of justness and fairness.” Giang and colleagues (2024) created a framework for integrating equity into environmental modeling, showing how models can explore the implications of adopting different conceptions of fairness (equity) without requiring consensus on which normative position is correct.

Why This Matters for Sustainability Science

There are several reasons why this two-step approach to conceptualizing the relationship between (in)equality and (in)equity is important for the field of sustainability science. At the same time there are also some tradeoffs I will get into below.

Inequality can emerge without prior injustice

One common assumption is that inequality is caused by inequity—that unequal outcomes require upstream injustice to explain them. But both theory and empirical evidence suggest that substantial inequality is an emergent property of all complex adaptive systems (Clark & Harley, 2020). Marten Scheffer and colleagues (2017) demonstrate this point compellingly. Imagine identical people foraging on a landscape where resources are unevenly distributed—some patches rich, others barren. Everyone has the same abilities; no one cheats. Yet inequality emerges anyway, because where you happen to start determines what you can harvest, and what you harvest determines where you can go next. Small advantages compound; small disadvantages trap. In a finite world with uneven resources, significant inequality arises from luck alone—from heterogeneity and chance, not from anyone’s wrongdoing. Once it exists, inequality tends to be self-reinforcing: incumbent actors seek to fortify their dominant positions of wealth and power (Beckert, 2022), and cultural processes reflect and reproduce inequality (Lamont, Beljean, & Clair, 2014). But these dynamics of consolidation are not required to produce inequality in the first place.

Iris Marion Young’s work on structural injustice makes somewhat similar point: injustice can emerge from “normal” processes in which no individual actor does anything wrong. In global apparel supply chains, consumers, retailers, and manufacturers each follow standard market logic—yet the cumulative result is workers laboring under exploitative conditions that no single actor intended or directly caused (Young, 2006).

Both Scheffer and Young complicate the assumption that unequal or unjust outcomes require prior wrongdoing.These insights highlight why causal stories that describe inequality as a result of inequity are not supported by what we know about complex adaptive systems. They don’t mean that there is no relationship between the two terms, but that generalizable assumptions about causality are not useful.

Different theories of justice need common ground

People hold genuinely different theories of justice—libertarian, utilitarian, egalitarian, capabilities-based, relational, Indigenous, and more. If we embed one theory’s verdicts into our empirical categories, we can only work productively with people who already share our commitments. The two-step creates common ground: we can agree on the facts of a distribution while openly contesting what justice requires in response.

Consider the two dimensions of equity that have been central to sustainability discourse since the Brundtland Commission: intragenerational equity (fairness within the current generation) and intergenerational equity (fairness between current and future generations). Both require the two-step approach.

For intragenerational equity, we can measure how environmental burdens—air pollution exposure, climate vulnerability, access to clean water—are distributed across communities and social groups. But determining whether those distributions are inequitable requires normative argument about what a fair or just distribution would look like or what theories of justice and fairness the actors involved in the situation chose to follow (ideally at least from my perspective through some sort of small-d democratic process.

For intergenerational equity, the case is even clearer. We can model projected climate impacts on future generations or track the depletion of natural capital over time. But what we owe future generations—the appropriate discount rate, whether natural capital can be substituted with other forms of wealth, how to weigh present needs against future ones—involves deep normative disagreement that cannot be resolved by measurement alone.

Tradeoffs with this approach

I cannot argue that there are not tradeoffs to this two-step approach. Approaches that embed normative judgment into measurement categories have real mobilizing power. Each January, Oxfam releases a flagship inequality report timed to the World Economic Forum in Davos—reports with titles like “Inequality Inc.” that generate global headlines with striking statistics about billionaire wealth. This work matters: it keeps inequality visible in public discourse when it might otherwise fade from view. But Oxfam rarely uses “inequity” at all. Instead, they build the normative judgment directly into “inequality”—framing it as a “choice,” as “economic violence,” as inherently unjust. The measurement is the indictment.

For advocacy aimed at audiences who already share certain commitments, this works. But sustainability science faces a different challenge: building coalitions across people who hold genuinely different theories of justice. For that work, the deliberative space the two-step creates matters more I believe.

Advantages of the two-step approach to (in)equality and (in)equity

For sustainability science, the two-step approach to conceptualizing (in)equality and (in)equity has important advantages:

Researchers can measure distributions of environmental burdens, resource access, and adaptive capacity without first having to resolve contested normative questions. The descriptive and evaluative tasks remain connected but distinct. This matters because normative questions are genuinely hard, and waiting to resolve them before doing empirical work would paralyze research.

When inequity is treated as a separate normative judgment rather than a property embedded in certain inequalities, multiple theories of justice can engage the same empirical findings. For a field that works across diverse cultural and political contexts, this flexibility is essential.

Figure 3: Same Inequality, Different Equity Judgments. The same empirical finding about air pollution exposure by income quintile receives different verdicts depending on which theory of justice is applied. The two-step creates space for deliberation about which framework applies and why.

The two-step also makes values transparent. When researchers or practitioners claim that some distribution is inequitable, they are making an argument, one that can be examined and contested. The framing invites deliberation rather than smuggling normative conclusions into empirical categories.

Finally, coalition-building may be easier with the two-step approach. People who disagree about theories of justice can still collaborate on establishing shared facts.

Using the two-step in practice

When describing sustainability outcomes, report inequalities as what they are: empirical findings about distributions. Who has access to clean water? How are climate risks distributed across populations? What are the patterns in environmental health burdens? These are questions that can be answered with data, and the answers do not require first settling contested normative debates.

When making claims about inequity, be explicit about the normative work you are doing. Why is this distribution unfair? According to what conception of justice? What would a more equitable distribution look like, and by what criteria? This transparency opens space for genuine deliberation about values rather than obscuring it.

And when encountering these terms in other literatures, pause to ask which framing is operating. Is the author treating equity as differentiated treatment aimed at equivalent outcomes (Froehle)? Using “inequity” to mean a subset of inequalities (Whitehead)? Assuming a causal relationship between inequality and inequity (which may be valid in a given context but is almost certainly not generalizable)? Its also worth remembering that the same words carry different meanings across fields, and recognizing this can prevent unnecessary confusion.

The goal is not terminological policing but analytical clarity in service of the intra- and inter-generational justice that sustainability science supports.

Notes

Note 1: Froehle’s original image was posted to Google+ in December 2012. The panels were labeled “equality to a conservative” and “equality to a liberal.” Later adaptations—not by Froehle—first relabeled them as “Equality” and “Fairness,” then as “Equality” and “Equity.” Froehle’s own retrospective (2016) traces these mutations with bemusement but does not engage the terminological question directly, because the image was never about the relationship between (in)equality and (in)equity. It was about normative contestation over how different groups (in this case political parties) understand fairness. That said the “Equality vs. Equity” version is the one that went viral and therefore had this enormous influence on popular understanding of these terms.

References

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics, Book V.

Beckert, J. (2022). Durable Wealth: Institutions, Mechanisms, and Practices of Wealth Perpetuation. Annual Review of Sociology, 48, 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-030320-115024

Braveman, P., & Gruskin, S. (2003). Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(4), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.4.254

Clark, W. C., & Harley, A. G. (2020). Sustainability Science: Toward a Synthesis. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45, 331–386. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-043621

Froehle, C. (2016, April 14). The Evolution of an Accidental Meme. Medium. https://medium.com/@CRA1G/the-evolution-of-an-accidental-meme-ddc4e139e0e4

Giang, A., Edwards, M. R., Fletcher, S. M., Gardner-Frolick, R., Gryba, R., Mathias, J.-D., … & Tessum, C. W. (2024). Equity and modeling in sustainability science: Examples and opportunities throughout the process. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(13), e2215688121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2215688121

Hamann, M., Berry, K., Chaigneau, T., Curry, T., Heilmayr, R., Henriksson, P. J. G., … & Wu, T. (2018). Inequality and the Biosphere. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025949

Jasanoff, S. (2004). States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. Routledge.

Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S. V., & Almeida-Filho, N. (2002). A glossary for health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(9), 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.56.9.647

| Lamont, M. (2018). Addressing Recognition Gaps: Destigmatization and the Reduction of Inequality. American Sociological Review, 83(3), 419–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418773775 | Open access |

Lamont, M., Beljean, S., & Clair, M. (2014). What is Missing? Cultural Processes and Causal Pathways to Inequality. Socio-Economic Review, 12(3), 573–608. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu011

Marx, K. (1875). Critique of the Gotha Programme. Full text

Milanovic, B. (2016). Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Milanovic, B. (2023). Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War. Belknap Press.

Minow, M. (2021). Equality vs. Equity. American Journal of Law and Equality, 1, 167–193. https://doi.org/10.1162/ajle_a_00019

| Norheim, O. F., & Asada, Y. (2009). The ideal of equal health revisited: Definitions and measures of inequity in health should be better integrated with theories of distributive justice. International Journal for Equity in Health, 8(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-8-40 | Open access |

Pierson, P., & Lamont, M. (Eds.). (2019). Inequality as a multidimensional process. Special Issue of Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 148(3).

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century (A. Goldhammer, Trans.). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Piketty, T. (2020). Capital and Ideology (A. Goldhammer, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

Putnam, H. (2002). The Collapse of the Fact/Value Dichotomy and Other Essays. Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press.

| Scheffer, M., van Bavel, B., van de Leemput, I. A., & van Nes, E. H. (2017). Inequality in nature and society. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(50), 13154–13157. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706412114 | Open access |

Sen, A. (1979). Equality of What? Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Stanford University. Open access

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality Reexamined. Harvard University Press.

UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination. (2017). Leaving No One Behind: The UN System Shared Framework for Action. United Nations. https://unsceb.org/sites/default/files/imported_files/CEB%20equality%20framework-A4-web-rev3.pdf

Vallgarda, S. (2006). When are health inequalities a political problem? European Journal of Public Health, 16(6), 615–616. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckl047

Whitehead, M. (1992). The Concepts and Principles of Equity and Health. International Journal of Health Services, 22(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN

Willis, R., Curato, N., & Smith, G. (2022). Deliberative democracy and the climate crisis. WIREs Climate Change, 13(2), e759. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.759

Young, I. M. (2006). Responsibility and Global Justice: A Social Connection Model. Social Philosophy and Policy, 23(1), 102–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265052506060043