A Framework for Research in Sustainability Science

Sustainability science draws from an extraordinary range of perspectives—ecology and economics, political science and engineering, indigenous knowledge and systems thinking. This diversity is a strength, bringing complementary theories and methods to bear on the challenge of sustainable development. But it has also left the field somewhat fragmented into distinct research programs, each with its own terminology, conceptual frameworks, and favorite case studies.

Consider just some of the traditions that have shaped our understanding: resilience thinking, with its focus on social-ecological systems and tipping points; industrial ecology, tracking flows of energy and materials through economies; environmental justice scholarship, highlighting how pollution and environmental harm fall disproportionately on marginalized communities; research on socio-technical transitions, examining how societies shift between technological regimes; and work on livelihoods, emphasizing how local actors secure access to resources. Table 1 lists eighteen such research programs that have most influenced the field—each making distinctive contributions, yet often talking past one another.

| Name | Special contribution(s) |

|---|---|

| Complex adaptive systems (CAS) | Local action by heterogeneous agents, constrained by higher level structures, central role of innovation/novelty |

| Coupled human and natural systems (CHANS) | Reciprocal links between human and natural systems, special attention to links across space |

| Coupled human-environment systems (CHES) | Place-based analysis of linkages, emphasizing physical and biotic environment; actors and agency |

| Earth system governance (ESG) | Importance of institutional design, agency, and power for governing nature-society interactions; emphasis on transitions and inequality |

| Ecosystem services/natural capital | Goods and services flowing from functioning ecosystems; role of institutions and technologies in shaping production and access |

| Environmental justice (EJ) | Focus on inequality and environmental harm, vulnerability of marginalized communities, maldistributions of power |

| Feminist political ecology | Gender analysis of environmental change and resource access; intersections of gender, power, and ecology; attention to embodied and situated knowledge |

| Industrial ecology/social metabolism/circular economy | Use of energy and biophysical resources, flows in and out of manufactured structures, technology design, trade |

| Innovation systems/evolutionary economics | How innovation emerges and diffuses; national and regional innovation systems; role of public sector in shaping direction of technological change; mission-oriented innovation policy |

| IPBES conceptual framework | Focus on biodiversity benefits for people, collaborative processes for mobilizing multiple values and knowledge systems |

| Livelihoods | Local actors’ entitlements and capabilities to secure access to resources; role of agency, power, politics, and institutions |

| Pathways to sustainability | Emphasis on poverty alleviation, local knowledge, and social justice; power, politics, problem framing, and narratives |

| Resilience thinking | Social/ecological systems as CAS displaying multiple regimes, tipping points, coping with risk, adaptive capacity |

| Social-environmental systems | Co-production of useful knowledge by actors and analysts, boundary work, trust, power, monitoring, feedback |

| Socio-ecological systems (SES) | How actors use resources in particular contexts, role of institutions in governance outcomes, multi-level linkages |

| Socio-technical transitions/MLP/SNM | Technology change as multi-level evolutionary process; transitions among regimes, path dependence, incumbent actors |

| Sustainable consumption-production (SCP) | Joint consideration of coupled consumption and production activities, beyond control of pollution alone |

| Welfare, wealth, and capital assets | Well-being across generations linked to wealth defined by access to resource stocks; substitutability among stocks |

Table 1: Research programs that have shaped sustainability science. Adapted and extended from Clark & Harley (2020).

Over years of working across these communities, my colleague Bill Clark and I developed what we call a “Framework for Research in Sustainability Science.” Our goal was not to create a grand unified theory—the field is far too context-dependent for that. Instead, we aimed to synthesize the elements and relationships that researchers across these many traditions have found useful for understanding how nature and society interact, and how those interactions might be guided toward more sustainable outcomes.

Think of the framework as a checklist: a set of building blocks that experience suggests are worth considering when analyzing any sustainability challenge. Not every element will matter equally in every case. But the framework reminds us not to casually overlook factors that have proven important elsewhere.

Reading the Framework

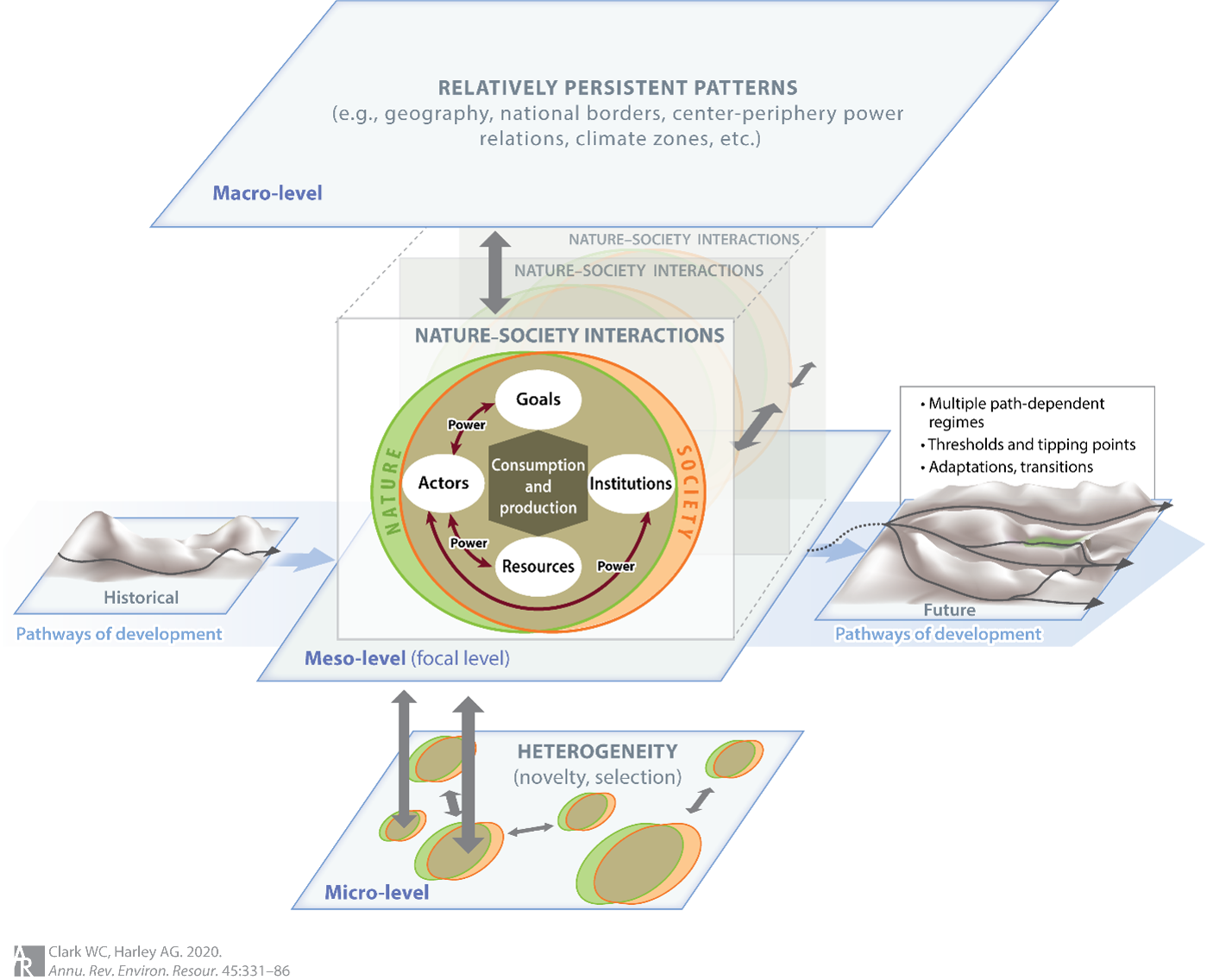

The framework is best understood visually. Figure 1 synthesizes the key elements and relationships into a single image that deserves careful study.

Figure 1: Framework for Research in Sustainability Science. From Clark and Harley (2020), Annual Review of Environment and Resources.

Figure 1: Framework for Research in Sustainability Science. From Clark and Harley (2020), Annual Review of Environment and Resources.

Let me walk you through it.

At the Core: Nature-Society Interactions

Start at the center of the figure, where you’ll see the intertwined nature-society interactions depicted in a circular diagram. The Brundtland Commission articulated the foundational insight decades ago: environment and development are inseparable. Recent research has shown just how thoroughly nature and society are intertwined in deeply coevolutionary relationships. Understanding whether development is sustainable requires examining the integrated pathways that emerge from nature-society interactions.

The four ovals within that central circle identify the key elements involved in these interactions:

Goals represent what people want from development. While the specific constituents of well-being vary across groups and times, a shared vision has emerged focused on the equitable advancement of human well-being within and across generations.

Resources are the capital assets—both natural and human-made—that society draws upon to achieve those goals. These include not just forests, fisheries, and minerals, but also manufactured infrastructure, human skills and knowledge, social institutions, and accumulated scientific understanding. One of sustainability science’s most important findings is that natural and anthropogenic resources, together with the dynamic relationships among them, must be treated as joint foundations for human well-being.

Actors are entities with agency—the ability to choose and decide. They include individuals, communities, firms, governments, and other organizations. What makes actors central to sustainability is not just their capacity to consume and produce, but their ability to articulate goals, construct narratives, and influence which institutional structures are in play.

Institutions are the rules, norms, rights, and widely shared beliefs that shape how actors behave in their relationships with one another and with nature. Much sustainability research evaluates how changes in institutions—say, a new fishery regulation or carbon pricing policy—affect prospects for achieving sustainability goals.

Notice how these four elements are bound together through relationships of consumption and production at the center of the diagram. But look also at the red arrows labeled “Power” connecting actors to goals, actors to resources, and institutions to resources.

The Role of Power

Power—the ability of some actors to affect the beliefs or actions of others—mediates the relationships among the framework’s elements.

Power can both constrain and enable what people think and do. It operates through multiple dimensions: the control of resources that allows some actors to compel others; the ability to shape institutional rules and exclude others from decision-making; and the capacity to influence goals, values, and even what counts as legitimate knowledge. Understanding how power differentials reinforce unsustainable development pathways—and how they might be challenged—is increasingly central to sustainability research. (I explore these dynamics more fully in a separate post on power and sustainability.)

Context Dependence: Multiple Systems in Play

Now look behind the central nature-society diagram. You’ll notice additional ovals receding into the background, each representing other nature-society systems. This visual choice emphasizes one of the most consistent findings across sustainability research: context matters enormously, and multiple systems are always in play simultaneously.

The development pathways that emerge from nature-society interactions are almost always dependent on the particular configurations of actors, institutions, resources, and historical legacies at work in a given situation. Each focal system we study—whether a particular fishery, farming community, or urban region—exists alongside other systems, each with its own variants of goals, resources, actors, and institutions.

These systems connect horizontally through flows of pollution, trade, migration, and the spread of innovations and ideas. Being specific about the particular interactions we’re studying while keeping these broader connections in mind is essential for useful analysis.

Three Levels: Micro, Meso, and Macro

Step back and look at the figure’s overall structure. The nature-society interactions we’ve been examining sit on the middle plane, labeled “Meso-level (focal level).” But this focal level is sandwiched between two others.

Above it, the Macro-level plane represents relatively persistent patterns that constrain what happens at the focal level: geography, climate zones, national borders, prevailing power relations, and other slow-changing structures. These macro-level forces press down on focal systems, shaping the conditions within which actors operate.

Below, the Micro-level plane depicts heterogeneity—the diversity and individuality of elements that are often aggregated away at higher levels. Here is where novelty emerges: new technologies, institutional experiments, social movements, and innovative practices. The small varied shapes on this plane, with arrows pointing upward, represent how micro-level diversity can bubble up through selection processes to reshape the larger system.

This hierarchical structure is not imposed artificially—it emerges from the complex adaptive character of the Anthropocene system. The vertical arrows connecting the three planes remind us that understanding sustainability requires attention to connections across levels: how macro forces constrain local possibilities, and how local innovations might scale up to transform established patterns.

Path Dependence, Regimes, and Tipping Points

Finally, look at the two landscape diagrams flanking the central framework—one labeled “Historical” on the left, one labeled “Future” on the right. These depict pathways of development as trajectories across a terrain of valleys and ridges.

The valleys represent regimes—characteristic sets of behaviors driven by particular dominant relationships and feedbacks. Within a regime, small perturbations tend to encounter forces that push the system back toward its earlier state or lock in its current trajectory.

The ridges separating valleys represent thresholds or tipping points. When a system operating near such a threshold experiences weak internal feedbacks, even small disturbances can shift it into a neighboring regime and thus onto a qualitatively different development pathway.

The black line traces a development pathway through this landscape. Notice how it mostly follows valleys—this is path dependence in action. Adaptation keeps development pathways within their original valleys in the face of shocks.

But look at the future landscape more carefully. The pathway crosses a ridge into a different valley—this represents transformation, the rarer crossing from one regime into another. Notice too the small green patch the pathway traverses. This represents an unstable area—would-be transformational changes can falter if they fail to cross fully into a new stable regime. A system might cling to an unstable trajectory for a time before eventually falling back into its original valley.

A Checklist, Not a Prediction

I want to emphasize what the framework is not. It is not meant to predict outcomes or serve as a grand theory of everything. The complex adaptive character of the Anthropocene means that development pathways cannot, even in principle, be fully predicted in advance. Innovation, surprise, and the unfolding unknown are permanent features of the system we inhabit.

Instead, the framework highlights what researchers across many traditions have found useful to examine when studying how nature-society interactions unfold in different contexts. It serves as a checklist—a first step toward asking how we might understand, and perhaps transform, nature-society systems onto more sustainable development pathways.

The central implication of treating the Anthropocene as a complex adaptive system is that sustainable development can realistically be pursued only through an iterative strategy that combines thinking through and acting out. Effective strategies must use science to help identify interventions likely to promote sustainability, but must also foster capacities to implement those interventions, monitor results, and take corrective action in an ongoing process of learning and adjustment.

Using the Framework

When approaching any sustainability challenge, the framework prompts a series of questions: What goals are at stake, and for whom? What resources—natural and anthropogenic—are being drawn upon? Who are the relevant actors, and how are institutions shaping their behaviors and interactions? How does power mediate these relationships? What are the relevant horizontal connections to other systems? What sources of novelty and innovation are emerging at the micro-level, and how might vertical connections allow them to scale up and transform established patterns? What historical path dependencies constrain current options? What might push the system across thresholds into different regimes?

No single analysis can address all these dimensions equally. But the framework reminds us that overlooking any of them risks missing something important. It invites us to situate our particular research questions within the broader enterprise of understanding and guiding nature-society interactions toward more sustainable futures.

This post draws on Clark, W.C. & Harley, A.G. (2020). Sustainability Science: Toward a Synthesis. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45, 331-386.